GD writes: This week, our new columnist, CommonMan, explains the iTaukei concept of vulagi, which he says has been widely misunderstood and deliberately politicised to create ethnic division in Fiji.

He says vulagi actually means “honoured guest” more than foreigner or visitor. But he goes on to raise a question many non-iTaukei are also asking: “When does a vulagi cease being a vulagi in the land of his or her birth and becomes a kai Viti?”

It’s a question the nation as a whole is still grappling with – the issue of who genuinely belongs. And as it does, CommonMan gives us an insight into grassroots iTaukei thinking from his vantage point in the vanua .

As I explained last week, he is a farmer, village dweller and commoner from rural Viti Levu with a distinctly uncommon ability – thanks to his schoolteacher mother who instilled in him a love of reading – to both express himself in the English language and enlighten.

I personally learnt a lot from this. Read on…

—————————

VULAGI – FOREIGNER OR GUEST

The intense debates that have raged and continue to rage over very elementary issues that were never a problem before is symptomatic of how highly polarised, even toxic, the national political landscape has become over the past couple of years.

My first Grubsheet article last week evoked some of the same kind of response. It is surprising how a simple introductory text could be so easily misconstrued to mean something else entirely. But it is also evidence of the unresolved feelings, or more accurately, the lack of meaningful closure most people have about issues they deem important. The conversation surrounding the use of ‘vulagi’ is a prime example.

The term vulagi has been so heavily politicised that it has lost its true cultural meaning. In iTaukei sociolect, it means a guest, more than it does a foreigner, due fundamentally to three things: one, its definition, two, the emotional imagery the word evokes which is that of an honoured guest, without any extra references to race, gender or identity. Three, its cultural historical evolution and usage. This piece serves to postulate evidence of this.

It is also perplexing that none of our politicians or technocrats have stood up to address it. It seems they intentionally allow this mischaracterisation to persist because it plays into the larger narrative of identity politics, a tactic called race hustling. They exploit racial situations to serve their own political interest and to stay relevant. In addition, the silence or ambiguity of our iTaukei academics only serves to fan the fires of division.

‘Vulagi’ is composed of two root words, ‘ vu‘ and ‘lagi,’ an abbreviation for ‘vumailagi’ in Bauan or ‘vunilagi in the Western dialects. Both amount to the same thing. ‘Vumai’/‘vuni’ meaning ‘originating or to come from’ and ‘lagi‘ – the skies.

It is interesting to note that most Pacific Island countries use lagi to mean heaven, sky or both, be it Melanesia (Vanuatu, Solomon Islands, parts of PNG), all of Polynesia (Tonga, Samoa, Maori, Cook Islands, Tahiti, Rotuman, Wallis & Futuna) and Micronesia (Gilbertese, Marshallese, Federated States of Micronesia). Only Hawaii adds an extra layer, lagi also denotes royalty.

To accurately delineate vulagi, it is pertinent to first understand the iTaukei concept of lagi. The ancient iTaukei were seafarers traversing the length and breadth of the Pacific Ocean traveling to settle or trade. They primarily relied on the stars, the sun and the moon to ascertain direction, navigate or orient themselves. The ancients also practiced some form of astrology and believed that ‘lomalagi’ or ‘heaven’ was another abode of the spirits.. The ‘bete’ or priests were the mediums through which the gods or spirits made known their will through ‘vakacuru’ or ‘possession’.

In short, they looked to the heavens with awe and reverence because from it they derived both physical and spiritual direction. And out of this reverence for the skies grew a plethora of names, such as Lutumailagi, Ralagi, Lagikula, Rogoilagi, Tubailagi; and other words with ‘lagi‘ as their root like ‘lagilagi’, which in its various contextual usages can mean ‘honour, glory, or victory.’

Even the names of some chiefly houses allude to the skies. For instance, the residence of Tui Nawaka in Nadi is ‘Na Lagi’ or ‘the sky.’ The Ka Levu’s residence is ‘Nakuruvarua’- two thunders and another surname of his family is ‘Vosailagi’ which is translated to ‘to speak from heaven.” The Tui Sabeto’s residence is ‘Erenavula’ – the moon bows.

But, as with all words, its etymology too changes over time, particularly post European contact; and has expanded to include ‘kai-Valagi‘ or ‘vakavalagi/valagi.‘ In iTaukei, the term ‘vaka’ is a prefix meaning ‘like’ or ‘akin to.’ But when it is used with ‘lagi,’ it refers more to where the Europeans came rather than the original ‘lagi,’ which means the sky. The prefix ‘vaka’ changes the whole dynamics of the word ‘lagi.’ ‘Vakavalagi’ means like or akin to ‘lagi’, but it is not ‘lagi’. In my opinion, the term ‘valagi’, which the iTaukei often generally translate as overseas, has more to do with being foreign than the term ‘vulagi.’

The closest approximation of how the ‘vulagi’ is treated in iTaukei culture is the “Melmastia” tradition of the Afghan Pashtuns. In iTaukei culture, guests are considered as under the host’s protection, and they go to great lengths to protect and provide for their guests, even at great personal cost to themselves. Hosts treating guests to the best and then having to drink tea and tavioka the next week is a normal occurrence in most villages.

Harming a vulagi however is a grave dishonour and can often lead to infighting after guests depart. Anyone found guilty of harming a guest is publicly shamed, ridiculed and even ostracised. I have personally witnessed public floggings in the village community hall at the Bose-Vakoro growing up in the 80s. Nowadays, it may be a rarity, but vulagis are still protected and served.

In ancient iTaukei culture, the vulagi was so revered that they were often given chiefly status and titles. The first Ka Levu of Nadroga, Wakanimolikula, is one famous example. He was found shipwrecked on Yanuca Island (where the Shangri-La Fijian Resort sits) by natives who had been sent there to gather seafood for a chiefly investiture.

Because he was vulagi, he was carried on the back of an elder from Nakabuta village to Lomolomo (up the valley road near present-day Lawai village). On seeing the guest, the incumbent chief directed that the guest be installed in his stead. To this day, whenever any agnate descendant of Wakanimolikula dies, a tabua is presented to the descendants of that ‘backpacking” elder as a token of eternal gratitude, for without him, Wakanimolikula would not have become chief. Stories of the installation of vulagi as chief are common in iTaukei folklore.

In the days before Christianity, it was believed that the spirits and gods, though having their abodes in lagi, could also live and walk as man. Fijian oral history is replete with stories of gods interacting directly with humans. The tradition of caring for the vulagi grew out of the ancient iTaukei wariness that they could be hosting gods as their guests, and so accorded them special treatment.

Over time, this custom became a normal feature of iTaukei life. The arrival of Christianity re-enforced this tradition. In the New Testament, Hebrews 13: 2 speaks of being “hospitable to strangers for by so doing some people have shown hospitality to angels unawares.” But, even this caution is based on the story of Lot in the Old Testament (Genesis 19) where in showing hospitality to strangers, his household was saved from doom.

Post-contact, the sinking of the indentured labour-carrying Syria in 1884 on Nasilai Reef, along coastal Rewa, presents another striking example of how the iTaukei treat their vulagi; and lends even more credence to the notion that they’re guests and not foreigners.

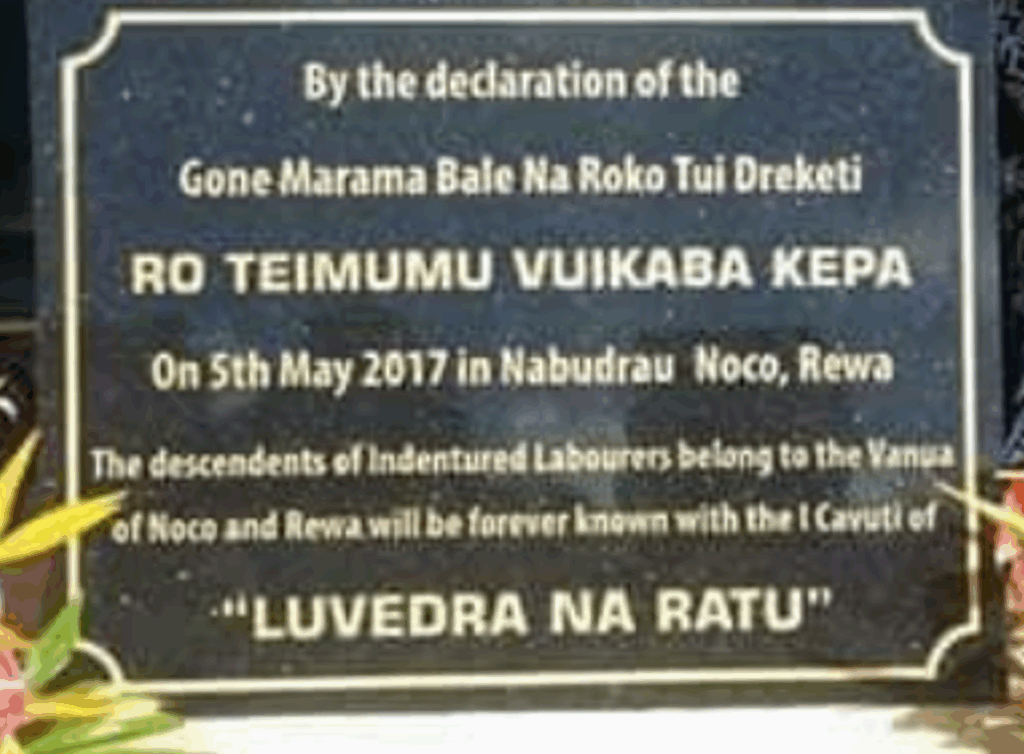

All the 38 who died were buried in the “sau-tabu,” or the chiefly burial grounds of the people of Naivilaca village of Noco District. Someone deemed a foreigner could not be accorded such an honour. In 2017, the Turaga na Tui Noco, together with the Gone Marama Bale na Roko Tui Dreketi, formally adopted the descendants of the Syria girmitya into the chiefly household of the Tui Noco and were titled as the “Luvedra na Ratu.”

This is an extension of an old iTaukei custom where vulagi were traditionally considered part of the chiefly household. Colonial administrators at that time assimilated this custom into their overall governance strategy. Almost all government stations were built near villages whose chief was also the head of a ‘tikina’ or district. Everyone in that station was considered part of the chiefly household. In all communal functions, they would participate with the chiefly household. It is still so to this day.

Last week ( October 5 2025) the Fiji Times printed a story of an Indian youth who, on arriving in Fiji in 1916, had a disagreement with his girmitya group and had promptly gotten himself lost in the woods. He was found and adopted by Ratu Meli Salabogi, who held the title ‘Turaga na Gonesau’ of Nabukadra village, Ra. The Turaga na Gonesau changed Bihar’s name to Ratu Timoci Kapaiwai and entered him into the Gonesau Vola Ni Kawa Bula.

Last week, the descendants of Ratu Timoci aka Bihar came to their village to perform ‘cara sala‘ and were warmly welcomed by their kinsman. ‘Cara sala‘ (translated: path clearing) is a ceremonial ritual performed by sons of a vanua who have not been to their village for a long period of time. This is yet another example of iTaukei treatment of the vulagi. An honoured guest and not a foreigner.

In daily usage, even as an iTaukei, in another person’s house, village, vanua, I would be considered their vulagi. In the introductions of guests to a function the term ‘vulagi dokai’ or ‘respected/honored guest’ is usually used. There is no way the term would be used on public occasions if it meant something racist.

The consistent abuse of the term vulagi as a political football has meant that the meaning of the term has evolved from a concept used to describe honoured guests and their incorporation into the larger vanua framework through chiefly adoption, protection and care; to where we are today. Now, vulagi is used to mark racial, ethnic or cultural boundaries. Although the word’s positive resonance has been weakened by politicisation, its historical and cultural uses demonstrate that its roots are honourable rather than derogatory.

In writing this article, I am compelled to confront a pressing question that naturally arises from this debate. In the long run, with regard to the larger context of race relations in Fiji, when does a vulagi cease being a vulagi in the land of his or her birth and becomes a ‘kai Viti?’ Is being vulagi a permanent condition? What are the parameters and requirements to belonging and true nationhood?

I leave you with images from the adoption of Luvedra na Ratu into the vanua and Noco/Rewa and the ‘carasala’ of Ratu Timoci’s progeny in Ra.

Plus the “calasara” ceremonies in Ra…

What are your thoughts on CommonMan’s article and the vulagi issue generally? Please tell us in the comments section below.

More from our new columnist next Sunday. Uncensored and authentic. A farmer sprouting ideas as well as his everyday produce.

Vinaka CommonMan

I now understand the origin, intent and use of the word “Vulagi” and the privilege that comes with it. You have provided a detailed explanation for that. You have looked into the politicisation of the word as well. I would like to see further writing on this to explore if this politicisation has moved further and created victimisation.

You have asked, when does a person belong?

What does it look like? Will the non itaukei really ever belong, both in the minds of the itaukei and that of the non itaukei?

Can Fiji have a shared culture, shared values (one that is not based on rugby or IDC)

Will people be able to ride above, create an inclusive society where we all belong?

I think Fiji is drifting away from being an inclusive society to a divisive one. There is division on a national level ( along racial lines), division within race and so on.

I do agree that the Vulagi issue is politicised and used for point scoring.

No-one born in Fiji should feel that they don’t belong.

I remember Frank saying along the lines of ” no one is a stranger- we all belong “.

Did not go down too well with the nationalists or the militant hindus like that gauri Jay Dayal.

Vinaka CommonMan. As a vulagi of Indian origin, I too think there was too much hysteria and wailing over the issue because certain politicians, like Mahendra Chaudhry, and his political advisor (and other things) Asha Lakhan, seized the opportunity to score political points. Politicians are the biggest problem in the country. When they are not wasting tax payers money, they are busy fermenting ethnic tensions for their own benefit.

अतिथि देवो भव (a-thi-thi de-vo bha-va): This is a Sanskrit phrase commonly used in India, meaning “the guest is like a god”. This God like status has correlations to the concept of Vulagi as explained above. 90s USP academics engaged with the politicised post 1987 usage as political hustle and analysed it as an ideological ism. VULAGISM.

Unfortunately the many incidences of the true hospitality and embracing of people that the Itaukei are rightfully famous for has been overshadowed by the racialized political usage. Interestingly the Leonidas Girmityas who were billeted at Waitovu near Levuka were the first to be such accepted as the Luve Ni Waitovu….still spoken of in its oral tradition.

This is what “reconciliation ” really looks like. Vinaka Sara na kena vaka macalataki.

It also aligns with my experience, more than 50 years ago, of being a genuine vulagi, not born in Fiji, arriving in a small remote village. It bears mentioning that while I was in the privileged position of being a young vavalagi, close relatives in another village some distance away, had some 40 years,or possibly more before that, welcomed permanently into their village an escaped girmit,a starving and naked man who had been hiding in the bush and raiding their gardens.

His capture disproved the “veli theory”, of why the yams in the garden were disappearing. His descendants are the living proof of that basic hospitality -or more- of which you write.

In the Fijian vernacular, the opposite of taukei (owner) is vulagi (visitor or guest).

The dichotomy was amplified (and politicised…perhaps unwittingly) when the Fiji First Government changed the title of the NLTB to i’TLTB. The difference between the i’taukei (owner) and vulagi (visitor or guest) was emphasised and made more stark.

It was politicised when a political candidate in 2022 referred to all non-i’taukei as ‘vulagi’. Elements of the politicised media with an axe to grind jumped at this and went hammer and tongs at a campaign to emphasise equal citizenry.

I was told at school that the term ‘valagi’ is the indigenous Fijian version of the English word ‘far land’. At first encounter with the white man indigenous Fijians asked them where they are from and the white man replied “we come from a far land”…hence the word ‘kai valagi’ …in the same way a Chinaman is referred to as a’kai Jaina’ or an Indian as a ‘kai India’, or a Tongan as a ‘kai Tonga’ etc etc

My own view is that anyone born in Fiji is a ‘kai Viti’ regardless of ethnicity. That translates to the larger nationality identifier as ‘Fijian’. I support this common label. It is an English label anyway.

One’s nationality (Fijian) is different from ones ethnicity (i’taukei, kai jaina, kai India, kai Loma, kai valagi etc – as used in everyday language).

We need to be sensible about this and agree that we have moved on from the early days of colonialism and have now matured into a modern nation where the common nationality should now be ‘Fijian’ where everyone enjoys equal rights before the law.

I do however, feel that we have to recognise the indigenous people as Fiji’s ‘first people’ and that we should adapt their culture and traditions as a virtue worthy of protection.

I couldn’t agree more with this, and especially your point about the need for the common identity – everyone Fijian – but the iTaukei being acknowledged as “first people” or “first Fijians”. Or to put it another way, first among equals but everyone belonging.

I believe that the indigenous people of Fiji have always been recognised as the first people of Fiji.

No one has taken that title or anything else from us.

Only ethno-nationalist politicians have been scaring us all these time that our land, our language, and our culture and tradition will be stolen from us. And now we have the sunset clause that will completely eradicate us from this earth.

Just a load of crap to further divide us as a nation and to keep certain people in power.

Sadly, most gullible itaukei still believe in this bullshit.

Words of deep wisdom and knowledge written by ‘CommonMan’ are few and far between.

Let’s hope they are not drowned out by the shallowness of vanity politics.

Fiji can choose to be whatever it decides to be, ideally supporting one another through successes and failures and be faithful to the values of equality and respect .

This is indeed an insightful and moving read – thank you CommonMan.

Words do shift in meaning and over decades detach from their original cultural intent and rich context.

Sadly you are correct in identifying that the word vulagi has become weaponised, and racial politics in Fiji serve only to keep corrupt leaders afloat.

Whilst some use of the word vulagi to express care and protection, some employ it to emphasise otherness and not belonging.

Most dangerous are those that mask racist behaviour behind words of inclusiveness, unity and all that was meant in the original meaning of vulagi.

When words and behaviour (both are forms of communication) do not match, manipulation is rife. We then need to put words aside and look at actions and behaviour.

Which current leaders in Fiji communicate inclusiveness and unity in their actions, behaviour, decisions and policies as they impact grassroots Fiji?

This article really is a master-class in cross cultural education.

Vulagi works for me. The word does NOT carry any taint of anything derogatory.

Let the cant of the religio-fanatic nationalists bray on. Its shelf is likely to be a short one.

That’s a deliberately short comment.

There’s no need to be either long winded or argumentative about the word ‘vulagi’.

CommonMan certainly likes to draw a king bow. He could have explained vulagi more simply and effectively.

The term vulagi is only ever used in third person, where it is a synonym for “honoured guest,” however, when used directly as in, “you are a vulagi,” this is always offensive period.

It’s like being cussed. So the ambivalent nature of the word will continue to remain for it has become ingrained the Fiji lexicon of swear words.

It will never go away. Non indigenous people just have to learn to take it.